Oral History

as told to Carl Mosher

for the Mill Valley Historical Society

October 14, 1978

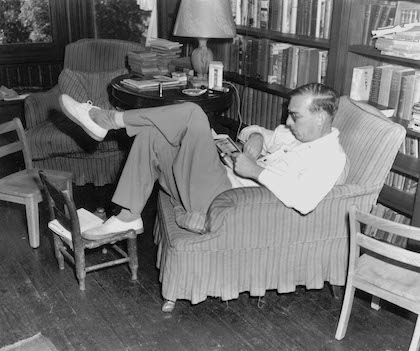

(Stanton Hill Delaplane was a travel writer, credited with introducing Irish coffee to the United States. Called "last of the old irreplaceables" by fellow-columnist Herb Caen, he worked for the San Francisco Chronicle for 53 years, first as a reporter and then as a columnist. He won a Pulitzer Prize for reporting in 1942.)

Trip with Herb Caen

Carl Mosher

This is October 14, 1978, and this is Carl Mosher talking to Stanton Delaplane in his Mill Valley home. For the past quarter century or so, give or take a few years, I've improved my temper and my breakfast in the morning by reading a daily column entitled Postcard by Stanton Delaplane. These Postcards are notable for their humor, their information, their anecdotes, and a general warmth that I've always admired and have found very comforting. The newspapers are generally full of sensationalism, and we need something that strikes a different note, that quiets the bile that's churning in the stomach; I find that Postcard does that for me. How do you do it?

Stanton Delaplane

Well, you sit down in the morning at about nine o'clock. This is the way I do it. Other guys may do it differently, but I don't think they do it much differently. I get up and make coffee, and I sit down. This is a very important thing--to sit down in front of the typewriter. Don't sit down in another corner, because if you do, you'll never hit the typewriter. Then I promise myself I'll just write one paragraph, because I really don't want to do this. After one paragraph it takes me about forty-five minutes, and I've got a column put away. It's not quite that easy, but I think that will give you the idea. Everybody has a different type of column; mine happens to be sort of an entertaining column. I have discovered that it's something like a comic strip in a way. People don't want you to change their picture of you. They don't want me to do politics, for instance. I don't make any political statements, and I don't come out for one thing or another. Herb Caen does. That's his way of doing it. Maybe some guy in New York does an entirely different thing. Like Earl Wilson, who hammers on the show business thing, "Who's at the Mocambo" or whatever the big club is at this time. We all have our thing. Herb Caen would die doing what I'm doing. So would Earl Wilson.

I spend a lot of time out of the country, so I'm sort of known as the "foreign guy." I do six months out of the country during the year; that is, two weeks out, two weeks back. A month out, a month back. People think of me as a man who really lives at home and is overseas. A traveling guy, but it's not home for him.

I tried to think of going overseas at one time. I went over and lived in London for a year because at that time we got $25,000 tax exempt if we lived overseas for two years. A lot of men I knew were doing it. Hank Ketchum, who does Dennis the Menace, was living in Geneva. Dick Condon, who did The Manchurian Candidate, still lives overseas, in Ireland now. A whole bunch of people were doing it. So, I thought, "Well, I'll make a million dollars, too. I'll save $25,000 dollars a year on taxes." I was doing pretty good at that time. I had some books out and things like that. And I was paying quite a bit of tax.

Book Signing in Macy's

I spent eleven months in London – nice house, family, children. I was doing fine except I couldn't stand it! I had to come back. This is home for me, that's all. I don't know why it works for some of the guys. For me, I have to have that little home atmosphere to keep a column going as much as anything else. For feeling, too. I can't make a go of it overseas. I begin writing like an expatriate American. John Crosby's doing that now. The guy who used to be the TV man in New York on the Herald-Tribune. I see he has just quit writing pieces from overseas. He's now writing a book. He was beginning to sound like an expatriate. I could recognize this in him right away because I'd done it myself. I know John pretty well so I could see what he was doing. I don't know; another man might be able to do it.

Hank Ketchum was able to stay in Geneva and do Dennis the Menace without any problems. On the other hand, he's doing a different thing. I'm doing a sort of day-to-day picture strip in a column. He’s doing a column in a picture every day, but he’s frozen his kid, he’s frozen his character. I’m writing about kids who are growing up and they keep changing every year. I’m taking them through Girl Scouts, Cub Scouts, and this and that. I’ve had two sets of children out of two marriages. Girl, boy, girl, boy, each time. I’m running out. I’m going to have to get married and have two more children. If I can get girl, boy, girl, boy again I’ll just keep it going.

Mosher

I know one of the techniques you use is delightful family tidbits and talk, which everyone enjoys and, of course, can all identify with, all of us who’ve had families.

Delaplane

That’s true. Everyone identifies with it because these things happen to all of us. I think people are surprised that it happens to somebody else the same way it happens to them. They think their experience with children is unusual; that kids can do these terrible things to you and be so blasé about it. They don’t think it could happen to anybody else. Then they read it in the column and say, “Gee, it happens to him, too.” It has kind of a good value, because it lets off a little steam for the guy or the woman who reads it. She says, “Well, it’s not just me with my children. It happens to everybody.”

Mosher

It’s very supportive in a way and reassuring.

Delaplane

I think it is.

Mosher

It’s one of the qualities that makes your column appealing and restful, as I was saying a minute ago.

Delaplane

It’s not something I plan. It’s not something I do thoughtfully. It’s simply something I do as I write. What I’m trying to do is write sort of an entertaining column about things that have happened to me and the way they happen. And it seems to have gone . . . well, it's been going on twenty-five years now.

Mosher

They turn out to be delightfully funny, too. You have a great feeling for lines and words.

Delaplane

I was the funny man on the Chronicle when I was a reporter. They gave me all the funny stuff to do, because I've got a little touch for that type of thing. When I was a reporter, I was writing the story of the chap who went up the flagpole and the firemen had to rescue him, that sort of thing. They liked that.

Mosher

You use an enormous amount of factual material in your columns. Even though they do have these other qualities we're talking about, the information is there, and this adds an interesting element. I don't think it would be quite enough to be all the other things we're talking about without this solid force of information that you keep adding.

Delaplane

You're talking about the overseas type of thing.

Mosher

It appears not only in your Sunday column, which is essentially travel, but I notice it's fed into your other columns, too.

Delaplane

Well, I try to pick up things that go on overseas, but I don't try to tell people exact prices or things like that. This is already being done in the papers where I'm syndicated, as well as in the Chronicle. What I try to do is complement that information with a little bit of what it feels like, but I think some solid information sneaks into it.

Mosher

A lot of it.

Delaplane

Like the fact that we used to leave our shoes outside the door at night. In England and all over the Continent you'd see all these shoes lined up. It kind of surprised me the first time I ever saw it. I said, "Somebody will steal them." But no, they don't. There's a man who comes by and polishes them.

With the great number of tourists now going through European hotels this doesn't happen. I've tested it a good many times by putting a dab of tooth powder on the heel of a shoe to see if it gets wiped off. The man always shows up for the tip when you leave, but the tooth powder is always still on there.

One time in Greece I was at the Athens Hilton. There's a little box you put your shoes into which can be unlocked from the outside. I put a pretty fair tip on the toe of the shoe and left it there for a week. Every night I’d leave it there, and it was never picked up. And the Athens Hilton is supposed to be a Class A hotel where everything should be done.

I think what it really is, this was the thing people were used to when they took the Grand Tour; when airplanes weren't flying, and they weren't taking millions of people around. These were little amenities that people expected when they came down from the country to London. They expected their shoes to be picked up and shined at night, and they were. But there weren't so many of them. It's not that the people now don't want to work.

Mosher

One of the characteristics of your columns, to me, is that they give off a feeling of effortlessness. They seem to be easy. I think nearly all things that are well done have that characteristic. It doesn't mean that they're slovenly, it means just the opposite. A tremendous amount of craftsmanship goes into it, of course. But I notice that you use more dialogue than most people, and lots of paragraphs. What is the reason for that?

Delaplane

I think it reads better. I've got a pretty good ear for dialogue, so I can remember it. Of course, the master of that was John O'Hara, who was a guy with the greatest ear for dialogue who ever wrote for anybody. I look through his stuff pretty good and studied other guys who have done it. And I've done it a lot myself. Now they teach me at the University of Missouri and the Columbia Journalism School—how to write dialogue.

We used to write in shorter paragraphs, or we tried to. I did it as a reporter because we had a very narrow column. I figured out if you had five lines in your lead it would be very difficult for a person to read it and digest it. Reading is a matter of your eye going over a whole paragraph at a time. If you are reading your own language, you don't read word by word; you digest the whole paragraph. So, I tried to split it. Punctuation splits a thought, so if you can drop in a period here and there it's a good thing.

When I write a column it takes me about forty-five minutes. That is the actual writing time. I just sit there, and, as soon as I can get the first paragraph, on it just goes. If I have to go more than an hour and half I throw the column away, because I figure it's going to be too labored. I don’t mean an hour. If it goes an hour and a half. If I've had to work that hard on it, I’m pretty apt to throw it away.

Mosher

You could use the material again, probably, but at a different time.

Delaplane

I might, or I might do a different thing. The idea, the feeling, that I've got on that one just doesn't go right. So, I might start over again and do something else. But when you're doing six a week, you don't throw them away too carelessly, you know what I mean? You kind of tend to hang on.

When I'm through working with a column, then I sit down and go through it. The main corrections I make are putting in more periods and more paragraphs. It's a little bit like I'm talking here. I'm talking without much punctuation. I find that when you transcribe this stuff onto paper—which I've tried to do when I dictate to my secretary—it doesn’t have enough periods in it. It doesn't have enough stops. And it doesn't have enough white space around it. It doesn't have enough eye appeal to make it easier to read so that your eye can grab the whole paragraph. This is pretty technical. It’s kind, of dull except for writers.

Mosher

No, I think it’s very interesting. Let’s take the opposite, a long, convoluted sentence like, let’s say, the late Lucius Beebe used to write. Contrast that with the sort of thing you do.

Delaplane

I can’t remember Lucius’ writing that well.

Mosher

He wrote very long sentences.

Delaplane

There are guys who can write long sentences and make it stick. For them it’s exactly right. Charles McCabe is a man who can use a lot of words that you don’t know; you have to look them up in the dictionary. Yet you can still read it and feel it.

I was having a drink last night with Charlie at the Washington Square Bar & Grill. We were talking about how people write, which is what all columnists do when they get together. This time we were both cutting up Warren Hinckle. Charlie’s idea was that Warren Hinckle starts off by getting a lawyer’s opinion which strikes a premise. Then he tears it apart and puts it together again. I don’t know how true that is. We notice each other’s styles, but we don’t try to imitate them. Some people do try to imitate in a general way. there’s no doubt that. Caen admits he was mostly influenced by Winchell. I don’t know who influenced me most, but I would say, if anybody, it was E. B. White on the New Yorker. His style probably influenced me more than anybody else’s.

Mosher

Great model. It’s interesting what you said about Herb Caen. I always considered Walter Winchell to be sort of a lowbrow, almost illiterate. Whereas Herb Caen writes, in his own way, a very erudite column.

Delaplane

I think Caen far surpasses Winchell. He’s much better now than Winchell ever was. Of course, Winchell was in New York at the right time of his life for that town, and he was amazingly powerful. He could fix a show so that it would run twelve more months, I mean a show that was dying. He would plug it, and it would run twelve more months. He didn’t plug it very much, either. He just gave it a good boost every once in a while, and people would go down and see it.

Mosher

He certainly knew what stimulated interest. This might be a good time to inquire about some of your column successes. I mean the more notable ones like the Ding Dong Daddy of the D Car Line, which I think must be an interesting story.

Delaplane

That was when I was a reporter. One day they handed me that story. I’ve forgotten how it broke. They were going to arrest this man for bigamy, that was the idea of it. There were two or three wives who had gotten together and found out that he was married to all three of them. His name was Francis Van Wie, I remember. He took it on the lam, so now he’s a fugitive. He was a harmless little guy, a kind of roly-poly, five-foot-two guy who was a conductor on the D carline [cable car], which was active at that time out on Union Street.

The Examiner had written a story on it, and they had tagged him as the “Car Barn Casanova.” When I grabbed the story, I tagged him as the “Ding Dong Daddy of the D Car Line.” Tagging people in a news story often makes them more readable to a person; like the “Buttermilk Killer.”’ I had him one time. Not a very good title, but it held up. Why the “Ding Dong Daddy’ held up better than the “Car Barn Casanova” I don’t know, but I think there’s no doubt that I took the story away from them.

Mosher

D is a stronger letter.

Delaplane

That’s possible. They say “K” is the strongest letter. That really picks up Hawaii, which is practically everything; Waikiki, Kamehameha. . .

Mosher

I can remember a column of yours many years ago, to illustrate how these things stick with one. You referred to a Japanese lady doing stripteases in the winter. It gets awfully cold in Tokyo, and you referred to her as “Miss Gooseflesh of 1959.” I thought that was hilarious. I still remember it.

Delaplane

You’ve got a better memory than I have. I’d forgotten that one. I sort of recall that we were sitting around talking to a bunch of these girls in some bar. They were dressed in some very undressed effects, low-cut, and they were all shivering.

Mosher

Buildings were pretty drafty for a number of years after the war in Japan. One of your accomplishments which I really wasn’t aware of, was your expedition to Mexico a number of years ago. What are the details there?

Delaplane

Well, I’d been on a trip down in Mexico. I ran into a taxi driver or bus driver who was a big Pancho Villa buff. I’d just had an accident out on the highway. I had hired a guy in Mexico City to drive me up. He was a fly-boy type of guy. He kept my car at about ninety miles an hour. Early in the morning a farm truck ahead of us started to make a turn. My guy was a Mexico City taxi driver, so he was going to swing around to pass. The farm guy decided to come back again, so he swerved back onto the road. We hit him at eighty miles an hour at least. Fortunately, he was going away from us, so it didn’t do any damage to him. My car was a wreck. I had to take it across the border. You have to take a car out of Mexico. We sold it in El Paso for junk, and I bought a new car.

But when we hit this guy, I had a whole bunch of pottery packed in the back end of the car, which was a station wagon, and it all came up and hit me in the back of the head. You know that Mexican pottery and how they pack it. There was busted stuff all over. That stuff busts easy, but my head didn’t.

Finally, a cop came up, and he flagged down a small bus. The bus driver was drunk as hell. God damn, he was drunk! Everyplace we came to, he wanted. to stop and get a tequila. I speak Spanish and I said, “I can’t stop, man, because I’m going to be questioned by the policia.” He said, “Oh, let me tell you about the little place where Pancho Villa did this and Pancho Villa did that.” He was telling the story, talking about what a macho guy Villa was.

He drove me into the small town where Pancho Villa had been killed. It’s called Hidalgo del Parral, a little bit of a town in the middle of the Chihuahua Desert. Indians come down to the town from the back country. It looks like something from a John Wayne movie. They’ve got long hair, bobbed, and they wear sort of a kilt instead of pants. They’re called Tarahumara. They haven’t changed much since the conquest.

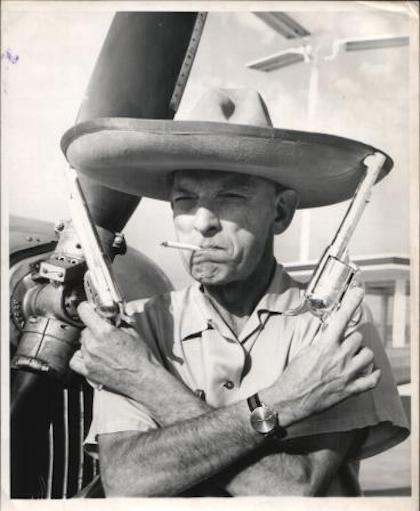

Pancho Villa Trip

After I’d straightened myself out, I was writing the story and found out they were going to hold a celebration for Pancho Villa the next year. I got the Chronicle to send us down. At that time Scott Newhall was editor of the Chronicle. He was a real gung-ho guy for stunts. He was what they call a “summer editor.” When nothing is happening, the summer editor will make something happen. Scott was a genius at that.

We got the Western Flying Sheriffs Squadron. I happened to know some guys, and we said, “Let’s fly down; we’ll have a big celebration and present Pancho Villa to the nation.” At that time there was a little doubt as to whether Pancho Villa was really a hero or not. The Mexican government was afraid to play him up on the hero’s list because he’d raided Columbus, New Mexico, and killed some GIs. But that was years ago.

So, we got the Western Sheriffs. We flew in about thirty planes full of guys. I got Trader Vic to fly in three chefs and a planeload of food, and we put on a big fiesta. We got Art Bell, who was the flower man in Maiden Lane, to get us 10,000 vanda orchids; you know, those little orchids they make leis of. We took a small plane and these veterans of Pancho Villa, who weren’t marching quite as fast as they used to in the Cucaracha days. That all happened in 1913 and ’14, and by this time they were a little bit ragged. But they were walking down the street in this little bit of a town, dry town. We flew over it with a staggerwing Beech, which will fly at about forty miles an hour and still maintain enough speed. We dropped these vanda orchids right alongside them out of the plane. They came down like little parachutes. God, they were really amazed!

We went out to Pancho Villa’s grave. The stunt of this actually was that Pancho Villa’s head was cut off after he had been buried out there in the cemetery at Parral where he was killed. He was shot down in an ambush. We got some of these veterans of Villa to fly over with our people and smoke-bomb the places where they thought Villa’s head might have been buried. We had some pretty good. information on this, and we were pretty sure it had never gotten over the border. While these guys were smoke-bombing various places, we were actually digging in another place. I hired a whole village of a hundred men, paid them a 1,000 in pesos, which was a lot at that time, 12,000 pesos.

Mosher

This was about 1961, I believe.

Delaplane

No, I’m pretty sure it was about 1968. Anyway, we dug around, but we never found Villa’s head. That was the hell of it. One of the bad things about the Flying Sheriffs is that it’s sort of a party. Let me show you this star. It says, “Sheriffs Air Squadron.” This one’s from Alameda County. There are Sheriffs Air Squadrons for everyplace. I’ve got a star from Marin, one from San Francisco, and I’ve got this. I carry this one around because it’s the best-looking.

Mosher

It’s a little like a posse, except that you’re flying instead of riding a horse.

Delaplane

That’s the idea.

Mosher

Well, that was quite a caper.

Delaplane

We got a lot of publicity out of it; we made Time and Newsweek. This is very valuable to a columnist because there are other newspapers whose editors read it, and sometimes you get your column into more papers.

Mosher

Didn’t you receive some special recognition for this?

Delaplane

I don’t think we got any recognition except we got a lot of national press.

Mosher

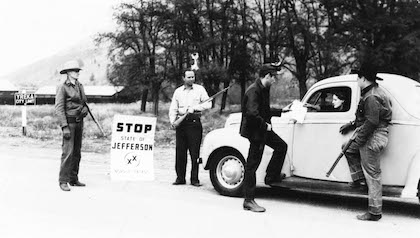

I can remember your Pulitzer Prize stories, which had to do with five counties in Oregon and Northern California trying to set up a new state, but I can’t remember any of the details. It would be nice to hear about that.

Delaplane

We got a little story on the AP wire one day saying that two or three counties up there were going to secede because they didn’t feel they were getting enough attention from the legislature. This was about two or three weeks before Pearl Harbor, just before December 7, 1941. They sent me up to Yreka where this was going on, and I began taking charge of it; I could see that they needed a little help.

Congratulations on Pulitzer Prize

We put up roadblocks and we declared a national holiday. No sales tax to the governor because “we have copper up here, and if he wants copper let him come up and dig for it himself.” A press agent kind of thing. It was really being press-agented by a guy from a little county in Oregon that had no railroad and no telephone. He described himself as the “hick mayor of the farthest west town in the United States,” which it was. He turned out to be a simple, barefoot press agent who used to work for Bell Telephone in Philadelphia. Pretty good. He had come out there and got himself elected mayor of Port Orford. He set up this thing for these counties. So, he was press-agenting it, and I was press-agenting it. We got together in a little cabin someplace in a small town up in Oregon.

Mosher

Compared notes.

Delaplane

Compared notes and decided how we would do it. The only thing the matter with it was he died the next day of a heart attack. The story itself ran for seven days. With the guy dying and then three or four days later we had Pearl Harbor, that stopped it. Otherwise, they would have dribbled along with it. It made a very dramatic ending to a seven-day series. This is what I think impressed the Pulitzer Prize Committee. If it had gone on, it would sort of have been going downhill. As it was, it went uphill all the way to a very high peak. The guy died, Pearl Harbor came on, and, when the Pulitzer Prize people read it, we were in the midst of war. We were getting shot to hell all over the Pacific. Our fleets were going down off Borneo and that sort of thing. It all looked very black. This story was the kind of thing that I think appealed to them—the last frontier, the guys up there packing guns, and things like that.

Mosher

It was relief, too, a contrast. Great theatre! Of course, you were assisted by some terribly important events.

Delaplane

There is no question about it. It was the right place at the right time. Which is what the most of anybody's business is—to be in the right place at the right time.

Mosher

How did they arrive at the name Jefferson?

Jefferson State Road Block

Delaplane

I don't know. It had been chosen before I got up there. I don't know who thought it up. There was a small bunch of people who were ready to play around with this. It was a kind of a half-serious thing with them really, but as soon as they saw their names in the paper and saw what was happening, they began to take it very seriously. Before that it was kind of for fun. Then they began to think, "Well, after all, this might be big."

I said, "Listen, you'd better get out on the highway." I wrote them a manifesto and we stopped cars with roadblocks, things like that. Everybody was armed with shotguns and carrying pistols but very polite. We would hand out the manifesto, which declared our rebellion against Sacramento and Salem in Oregon, and say, “Pass this out down the line.” We’d. give them a handful and say, “Every place you stop for gas, every place you stop for lunch, leave one of these on the counter.”

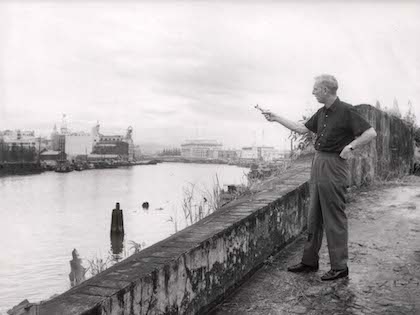

United Nations Conference: Stan Taking Notes with Arab Leader

Mosher

I wonder if lots of movements don’t start out more or less like that.

Delaplane

I believe they probably do.

Mosher

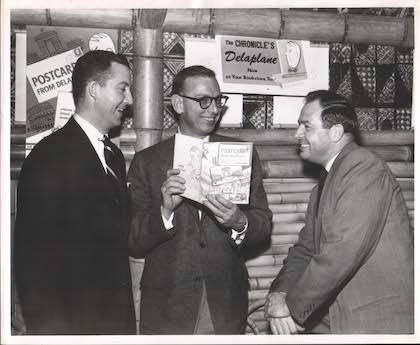

This might be a good time to discuss the name of your daily column, how you arrived at it, and some specifics like that.

Delaplane

Well, during World War II I was in the Navy. I’d been working in Washington, and I knew a lot of admirals, so I got myself put on inactive duty. The Chronicle and N.A.N.A., the North American Newspaper Alliance, wanted me to go overseas and do some stuff. That sounded better to me than what I was doing. I wanted to see something of this war and what was going on. So, I went out to New Guinea as a war correspondent for these people and covered the invasion of the Philippines. Then I got a wire from the paper saying, “Come back and cover the United Nations Conference.” (Delegates of fifty nations met in San Francisco, California, between 25 April and 26 June 1945 at the United Nations Conference on International Organization.) Came back for that. When that was over, I was reporting four-alarm fires, which didn’t appeal to me very much. There’s a time to quit in this business. The time to quit is after about ten years and I went fifteen.

Tokyo Rose Trial. Stan at Far Left End of Table

Somebody was taking a bunch of people over to the Holy Year in Rome. Flying the Atlantic was kind of an unusual thing at that time, it was about 1949 or ’50. They sent me over to write some feature stories.

The first place I went to was Paris. I was trying to figure out what I could put in the headline. I’d just done the Tokyo Rose trial, and I’d used the headline, “Tokyo Rose on Trial.” Being in Paris and wanting to be alliterative, I invented “Postcard from Paris.” They wanted to stay with that, so we made it Postcard from other places.

I went back and did straight reporting again on the paper, but then they sent me out again to Mexico. They began to get an idea that maybe they should keep this Postcard going. They took me off reporting and put me on salary. It took about two years before they did that.

Mosher

That would. be about when, the early fifties?

Delaplane

It was 1952 when the column became a standing feature in the Chronicle, and I was put on it full time. At the same time NcNaught Syndicate picked it up and began syndicating it and paying a royalty to the Chronicle, or a percentage of what they sold. NcNaught was one of the big ones. They had the 0.0. McIntyre column and Will Rogers Says column, two of the biggest of all times. The chairman of the board, a man in his late seventies at that time, had retired. He read some of my stuff and decided he was going to make me another 0.0. McIntyre. He thought I had that touch. He came out of retirement just to take on me. But it was the wrong time and the wrong place. He couldn’t quite make it go, and I couldn’t either. But I did all right in my own style.

Columns as a Book Character Drawing

Mosher

What was his name?

Delaplane

His name was really McNitt. He didn’t call it the NcNitt Syndicate because he thought that didn’t sound. very good. It sounded kind of like Boob McNutt. I think Boob McNutt was a comic strip at that time. He didn’t think McNaught sounded bad. He thought McNaught sounded pretty good.

Mosher

Do you remember when the Republican Party tried to rim Paul McNutt as a presidential aspirant? It was pretty generally agreed that it just didn’t sound right, and that killed it off. How about the line drawings of you that appear at the top of the column? When did they start?

Delaplane

When we were first running the column, we used to run, on the side there, baggage tags which would say SF0 to HNL—San Francisco to Honolulu—or whatever the place was. It had a kind of feeling of movement. Then they asked me If I wanted to run a picture, and I thought, No, I’d better not do that. Everybody’s picture that was in the paper had been taken about thirty years before! This tags you. Columnists will run a picture, as they do today, that was running thirty years ago. They don’t want to be known as having aged any, figuring people want them to remain as they are. And it’s true.

I said, “What I’d like to do is have a drawing made, a bunch of drawings, and we’ll sort of give it the feeling of a comic strip. This is a guy who is ageless, but he always had a little bit of a problem going for him. We had a very talented artist on the paper at that time named Dave McKay. I talked to Dave, and he drew up about ten drawings. From there on he drew more, and at the present time we’ve got something like fifty of them. I keep trying to get some more, but McKay has retired; I can’t get him anymore. Maybe he’s dead for all I know. I keep thinking I ought to change it, but you don’t want to change things too much. Syndicated columns, you don’t change the looks of your main character in a panel strip or whatever it is; you keep them the same.

Mosher

It’s dangerous to tamper with success, anyway. To me, as a reader of the column, those little drawings, simple though they are, set the tone for it to a remarkable degree.

Delaplane

I think so, too. I’d like to add about ten or fifteen more heads, but I can’t find anybody who can do it. I’ve had several guys work on it, but I can’t get what I want. It seems like it would be a simple thing because they are very simple drawings. You’d think you could just get some artist who could sort of copy that idea, the same thing. But the artists I’ve gotten all want to change it. They see it their way, and I want it seen my way. I haven’t found a guy who has seen it my way.

Mosher

Almost any time you take an idea to someone who considers himself a specialist, he’s bent on improving it. You probably get a lot of letters from readers. It would be interesting to hear a little bit about that.

Overseas with Daughter Kristin About 1953

Delaplane

The main letters that come to me are returns from the Sunday column, which is a “How to Travel,” a how- to- do-it column, a good deal of the time. I put in prices and places to go and things like that. I don’t try to slam it at them, but I tell them a little bit about a place. The Sunday column has a pretty good circulation; it’s running up to seventy-five and eighty papers right now and doing much better than the daily does as far as income return. The letters are mostly from people who are asking how to go about it. How do I do it? How do I go from here to there?

We have a system which I’ve worked out. We have a sheet on most of the places I’ve been in the world. It’s called Delaplane’s Private File for, say, Paris or for France. In it we give them three or four places to eat, what it’s like going through customs—do they shake you down much in customs—or anything like that. How much do you tip a taxi driver? How much do you tip the maid or the concierge? Four or five interesting little places that I’ve gone in France. We don’t give them a whole bunch of things like, say, a Fodor Guide does, but we’ll refer them to a guide and say, “If you want a real good guide on this thing, why don’t you buy Fodor or get the Michelin Guide, which will give you what you want. There are a lot of little things we might tell them, like maybe a little rip-off they might get somewhere that they might watch out for.

Mosher

Where do you keep this file you’re speaking of? And, who compiles it?

Delaplane

I do it. It’s all upstairs in my office. I keep an office in the house, and I have a secretary who comes in four hours a day in the morning. I sit down here and work, and she works up there. When we get the letters, I see practically all of them. If a letter is very easy to answer she will simply put the information sheet into an envelope herself and shoot it right out and say, “Stan said to send you this. There’s always something written on it. If I have it, I’ll write something on it, if it’s just one scrawl. We have a little gimmick called “Keep an eye on the bluebird,” which we use on this notepaper. It’s not really stationery, but sometimes we write on this to people if it’s a minor matter.

Mosher

Is this typed or in longhand?

Delaplane

It depends. Most of it is typed, but we’ll put some longhand on it somewhere. On these Private File things my secretary will write across the top of it, “Stan says to send you this.” But maybe the person has asked for something else besides what is in the file, like, “I’m very anxious to get a certain kind of China which my wife or my mother told me about.” Then we’ll write and tell her how to get it, or we’ll tell her how to go about getting it, say perhaps in Tokyo where you can get China hand-made with your own chop on it. I’ve had China made for myself, so I’ll tell them that. Then we’ll sign it off with a signature, or my secretary will say, “I talked to Stan, and he says to do this.” We make it pretty personal.

Mosher

I would expect most of the letters to you to be on the friendly side.

Delaplane

Yeah, I don’t get much on the downside.

Mosher

Some columnists get pretty heavy type letters.

Delaplane

Oh, sure. People go after McCabe all the time. This is part of his business. And Caen gets his. I think he was writing about it just the other day.

Mosher

As a matter of fact, yes.

Delaplane

People are chewing him out for this and that. My stuff is not controversial. What people write to me about mainly is, “You made a mistake about this.” When I wrote the other day about how to get your stuff traced by airlines, somebody wrote and said, “Yeah, for you they’ll do it, but they won’t do it for me. I’ve been trying for two years to get my pajamas back from TWA.”

Mosher

He may be right, too.

Delaplane

Of course! I wrote the guy and said, “Look, I know they do it for me, but this is the only way I know of that you can go about getting stuff returned. Airlines get so much heat from people that they have people working on this all the time to get it back. You won’t get it back any other way; the tourist bureaus in these countries won’t do it. I’m not saying I don’t get better treatment than you do, but I’m telling you that this is the only way you can do it.”

Mosher

You referred a while ago to the Paris File. Do you have similar files for each country that you go to frequently?

Delaplane

Practically every one.

Mosher

So, you have all kinds of information that you draw on. I noticed in a column just this week, on your most recent trip to Hawaii, that you not only told us about the island and how it’s currently progressing in its development and so on, but you also gave us information on luaus. I thought I knew about luaus, but you included information that I knew nothing about. For example, about how they secure the pigs for them, and this sort of thing. The native name for the hole they dig in the ground to put the pig in. I knew the routine, but I didn’t know that. I suppose you have all that information in your file or is it in your head?

Delaplane

Some of that sort of thing is in my head. A person who is going over to the Islands doesn’t really need to know about the imu and how it’s blessed by Pali; that you should get a kahuna to do it. I know all the things that you’re supposed to do, and I know that they really do this. Even the white people over there figure this is part of the ritual, and it won’t work unless you do it.

But the visitors aren’t going over there to dig a hole in the ground, heat rocks, have the pig blessed, and so forth, so I probably won’t include that in Delaplane’s Private File for Hawaii. But we might tell them which luau is the best one to go to, which happens to be the one up at Hana. It has more color, it’s more remote, it’s more Hawaiian, and it has much more feeling. The real slick ones are done down at, say, the Hawaiian Village on Waikiki, where they have the conch shell and a guy who walks through carrying the pig. The pig probably is never going to be cooked. because they’ve got them all cooking in the oven somewhere else. They couldn’t feed that many people with one pig. At Hana you’ll probably eat the pig they flew up in the airplane that day.

Mosher

Is the Honolulu area the greatest example you know of that we might call commercialized fun?

Delaplane

I think so. Sports Illustrated did a piece on Hawaii, and they called it “The Biggest Theme Park in the World.” It’s a pretty line. And it’s pretty true. It has been well “commercialized,” but everything’s been commercialized. They built Hawaii as a place for 3.4 million people to visit for the benefit of the 900,000 who live there. They have five islands.

Mosher

Where does it all stop?

Delaplane

I think it will just go right on. They have no intention of stopping it in Hawaii. This is the biggest income they have. They can’t go back to sugar because sugar is not as valuable as it was before. And sugar can’t support 900,000 people. When sugar was a big thing there were only 350,000 people in the Islands. When it got to be 650,000, sugar was still pretty good, but they were moving pineapple out, moving it to Taiwan and down to the Philippines. Dole was doing better raising pineapple down there. They’ve only got a little bit of pineapple going out of the Islands now.

All the beach land was sort of marginal sugar land. They raised some sugar, but they couldn’t raise it very far down. At one time they were raising a sort of mesquite down there to fuel ships with. You see it all over the Islands now. It was brought over from Texas originally, that scrubby mesquite that you see around the Southwest.

Nowadays a couple of people will build a place on the beach, a big hotel, a million-dollar hotel, Rockefeller and so forth. The State of Hawaii says, “All this beach land should be taxed. as priced.” Well, how the hell is Alexander & BaIdwin, the Parker Ranch. . . . This was marginal land; even the cattle couldn’t feed down there. Now they want to tax it at the same rate as the city centers. The owners have either got to get rid of the land, or they’ve got to build stuff on it. They have seen the point. You can build big hotels and condominiums on this kind of land, and you can sell it and make a hell of a lot of money out of it. In other words, you can build condominiums on that scrub land and sell them for 100,000 or 200,000 each if you have enough money to do it. And Hawaii has enough money to do it. People who own that land have that kind of money. If they don’t, they can certainly borrow it from each other, because they’re all interlocked. The Big Five is interlocked. They’ve intermarried, they’re interlocked in corporate structures. So, they go around and see Joe, and Joe says, “Sure, you can have a couple of million.” You put up a hotel, and there you go.

Mosher

How do you get all this information? You obviously talk to a lot of people when you’re traveling, picking up bits of information here and there, whether you’re in Hawaii or Glasgow, Scotland. You have in mind, I imagine, some sort of procedure and people you’d like to talk to.

Delaplane

I don’t really do a financial thing. This just comes to me in passing. I’m talking to some guy, and this is his business, and he tells me about it. I really don’t search for the financial structure of any country. I happen to know something about Hawaii. I’ve been there a lot, I’ve read. about it, and I’ve talked to guys who were in the business.

Mosher

I wasn’t thinking about finance in particular, although that’s part of it. I was thinking more of social customs and mores, and little interesting things that are peculiar to the particular place.

Delaplane

I don’t really know how I do it. I don’t work at it; I sort of let it come to me. I find, when I’m going out with people they will talk to me, and something will come up as they’re talking, and I’ll think, “Gee, I’ll check that out; that sounds like it might make a good story.”

Mosher

After all these years you’re probably a superb listener, something most of us don’t do too well.

Delaplane

I’ve got to use something the next day, so I listen. You listen, too. We all listen, but it depends on whether you’re going to use it or not. I might be listening to someone talking about how to start a new tennis ranch over in Hawaii. Another guy might think, “That’s a great idea.” I’m not particularly interested in tennis ranches in Hawaii, so probably that just passes me by.

Right now they’re talking about how they raise marijuana over in Maui, stuff called Maui Wowie. I think this is pretty good; a lot of people are going to read that. And I want some kid readers, too; I want the young readers. So, I find out how they do it, how they process it, and so forth.

Mosher

You just touched on a very interesting point. I imagine you have a greater range, as far as age is concerned, than any columnist in the business.

Delaplane

You mean personally? As I say, I’ve had two sets of kids out of two marriages, so I have them from thirty-five, my oldest girl, down to fifteen, my youngest boy. This is a fairly good range. I’ve seen kids go through different types of situations.

My older daughter listened to soap operas on the radio, Our Gal Sunday, The Third Mrs. Trent, or whatever it was. That type of thing. She listened to those all the time. Now my kids are looking at Bionic Man on color TV, which my older daughter didn’t have. She was a kid out of the listening age. These are kids out of the seeing age. People in this age bracket don’t have different mores, but they have a different slant on them, we’ll say.

Mosher

Your column is distributed in at least thirty-five newspapers. Do the letters you get from them indicate that teenagers as well as older people are reading you consistently? Or can you tell?

Delaplane

No, I can’t tell.

Mosher

Are there any perks you’d care to discuss that fall to the lot of a traveler like you?

Delaplane

Well, as the man said, “They will probably look up baggage for you a lot faster than they will for me; mine’s been gone for two years.” Sometimes the foreign offices for promotional travel will do things for you that they won’t do for other people. Actually, I can’t find that they do an awful lot.

Airlines will do quite a bit for you. Sometimes we’ll fly on a free trip. But one of the things about being syndicated is that you can’t fly on free trips because you’re always with a whole bunch of other guys. You find you’re traveling with, say, travel editors from three papers that buy your column. If you write about the place you’re going—for instance, you’re going to the Philippines and you have men from the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, and the Seattle Times—they’re not going to run what you write; they’re going to run what they write. So, I very seldom do that.

This means that a good deal of the time I have to pay my own way. I don’t get an expense account; I get a flat amount that I can use over a year. It’s around $20,000 that I can use without having to account to the paper or anything like that. I find this keeps me going pretty well.

Airlines are not supposed to fly you free unless you’re flying with a group which has been cleared by the CAB. Actually, at times they will come to you and say, “We would like to push a certain area, and we would like to have you come over.”

Mosher

What’s the implication there? That they’ll give you a free ride?

Delaplane

Yes, the implication is that they’ll give you a free ride, but they have to make some kind of excuse for it. They either put you on the payroll as a special assistant, or they buy your reprint rights. There are some things that the CAB will simply turn their heads away from, even though they may know it’s being done. But it’s not done very much; the CAB really won’t turn their heads away because there’s no advantage to them to do it. They really are trying to push these guys into line.

My expenses will easily run $20,000 a year, and most of the time it runs more than that. I have to pull it out of my syndicate money and hope that my syndication will improve in order to keep this going. It takes quite a while for syndication to improve that much, but sometimes you feel it's worthwhile.

I have some guys who go out for me once in a while. Sometimes there will be people on the Chronicle who are taking time off. I've got two or three of them I use from time to time on trips I think might go pretty well. I have a guy right now, a scuba guy, who is diving in Truk. There are about fifty wrecks there that we sunk in WWII in two raids—in February and April, I think they were. . .

*(Telephone rings)

I'm the answering service for all the fifteen-year-olds that phone here. This phone doesn't belong to me; it belongs to the kids, but I'm constantly taking messages. I put in a phone of their own, but when they go to sleep, they pull the plug on it because they don't want to get up in the morning. When there is no answer at that number up there, their friends call me, and I'm supposed to answer!

Anyway, this guy's diving down there now, and he sent me back a really interesting story on it. Not many people going into Truk; I think they had 4,000 people go through last year. But the word gets around, and a thousand of them came down to dive on these wrecks, which are all completely untouched. He was dropping down on one ship at 120 feet and found a whole bunch of zeros on the bottom of it. Ammunition all over the place, big cases, 50-gallon drums of aviation fuel. A bunch of bones, skulls, the whole thing. This place was just untouched. I don't do any scuba diving, so this is the guy I've got doing that.

I had a couple of guys down in the Amazon for a while; another diver and a reporter. It sounded like kind of a rough trip, so I thought, I don't think I'll do this one. I'll let somebody else do it. This guy came back through Bogota and picked me up a lot of information on the dope smuggling out of there. Colombia is the big place for cocaine now. This is the current big drug for people. They've gone off of heroin and onto cocaine, and most of it comes through Colombia.

Mosher

What are you going to do with all that information from Truk and from South America?

Delaplane

I've got the Truk stuff already written. He sent some of it to me. I may do some more with it. Stuff like Colombia I've been picking up from time to time. I have lunch every once in a while with a guy who's the head of federal narcotics "dangerous drugs" or whatever they call it. He's been out in the Far East for quite a bit, and he's back here now. When we have lunch, I learn a little bit about the drug traffic. I don't know what I'm going to do with it. Maybe when I get to Hong Kong I'll pick up a little something else about it, and maybe all of a sudden I can put a thing together. How Hong Kong works. How this stuff goes from Macao—I know a little about that. How stuff comes out of other places. You put together these little odds and ends, you stick them in your mind, and all of a sudden it comes to you that you've got a pretty good story. I don't know where it will come together. It might come together, say, when I'm talking to some guy in Tokyo in the Foreign Correspondents Club.

Mosher

Sort of like a jigsaw puzzle. Suddenly you say, "Hey, that's the piece that does it."

Delaplane

Somehow all these pieces come together. I've got a pretty good memory on these things. I've got a good filing system in my head that I can use to pull the stuff together. Sometimes, though, I won't come together on how to spell something. I'll be in a terrible position. I'll think, "I know that guy's name, but does McDougal end with two Ls or one?" Of course, we can send the stuff into the office and put a little (sp?) after it and they're supposed to look it up.

I was sending something out of London some time ago about a statue of Queen Boadicea, who was a Welsh queen who fought Caesar when he invaded the islands of Great Britain. I couldn't remember how to spell Boadicea, so I put a (sp?) after it. The guy who got it on the copy desk at the Chronicle changed it to Queen Elizabeth, probably thinking, what the hell's the matter with this bastard he doesn't know who's the queen of England? It was kind of a poetic line, too, "Where Queen Boadicea reins her marble horses." Son of a bitch changed it to Queen Elizabeth!

Overseas

Most of these things you can catch, but there are times when you run into things you just do not remember. Most of the time I can put things together and remember what somebody told me. But you don't have much time, when you're overseas and writing six a week, to phone people. And you don't have a library at hand in a lot of places.

There are lots of times when things seem to come up over weekends when nobody's working. Say I'm in Tokyo writing on Saturday and Sunday and the person I want to talk to maybe over at the beach or down in the Philippines for the weekend. I don't know exactly where to find him or where to find a library for that particular thing.

Mosher

You have reference material that you can use, but of course that doesn't take care of everything.

Delaplane

If I'm home, I can do it because I've got my files here—chronological files and subject files. I've got a pretty good filing system, so I can go into that if I'm writing here. But if you're sitting in a hotel room, even in the best place in the world like London where you can speak the language, it's still sometimes hard to get what you want.

Mosher

I remember you once referred to the fact that writing a column is the easiest part of the whole thing. I know that's an understatement, but I think you were talking about the fact that you have the syndication interest to consider, the union situation to consider. You referred to going away on a vacation and said that "vacation" should be in quotation marks.

Delaplane

I remember one time Herb Caen and I were talking about that. He said the hardest part for him is the administration of a column, which is the administration of a business, really. I'm not talking about the column as a writing thing; I'm talking about it now as a business thing. When I’m home I'll probably get two or three calls a day from people who want to have lunch with me. They want to have lunch because they want to talk about where they're going, or where their aunt is going. Or they want to get something in the paper. Caen has much more than that. I imagine he has ten calls a day from people who demand that he have lunch with them, because he has a great deal of power. When Caen mentions something in San Francisco he really pulls a lot of weight.

Then we have the union. The union says we must take five weeks of vacation a year. I haven't taken my vacation yet. While I'm taking a vacation from the Chronicle I still have to service the syndicate. The syndicate sells stuff by fifty-two weeks a year, and you have to appear all that time they have that space allotted to you. If I go on vacation now, and I write something that's pretty good—say the stuff I've got out of Truk, which I'm pretty happy with—it doesn't run in the Chronicle because I'm on vacation, but it runs in the other papers. Now what do I do? How do I make that stick? The Chronicle's my flagship paper, and I want that stuff to appear in the Chronicle. Do I give the syndicate second-rate stuff? Well, you don't want to do that, either. These are administrative problems which everybody has. I'm sure John Wayne and the other movie stars have the same situation. Of course, they can hire people who will do these things. I do hire a secretary who handles a good deal of it for me, but there is an awful lot of stuff you cannot get someone else to do. In other words, the person who wants to talk to me wants to talk to me. I can't have a second in command, an assistant, he can talk to. Caen has the same problem. They don’t want to talk to his secretary, they want to talk to Caen. They want to have lunch with Caen. They want to have lunch with me. So, we have sort of an overload that we can't delegate. We can delegate authority to somebody to do something or other, but we can't delegate ourselves to somebody else. It's particularly true for me because it's a very personal column. People who want to go somewhere, who want to send Aunt Emma somewhere, feel they should be able to talk to me and have me tell them how Aunt Emma can get the best buy in sheepskin rugs on the island of Mikonos. I know and I can tell her. I can even tell her to walk down the street, turn to the right, and there's a guy named Joe. Tell him you won't give him fifty dollars; you'll only give him twenty-five dollars. I can do that, but I can't spend my whole life doing that and still turn out a column, still go somewhere else, still keep the guy on tap down in Truk, who can't Telex because they don't have a Telex machine out of there and, of course, I want the stuff right now!

Mosher

Do you have a formula for picking out which things you do and which things you don't do?

Delaplane

I suppose I have a formula, but I don't know what it is. I guess it's kind of a God-help-us sort of formula. You do whatever is pushing you the hardest right at that moment. I never have found a system that makes life go easy, but I don't think anybody else has either.

Mosher

How have you resolved the dilemma you were talking about when you're doing material while you're on a sort of enforced vacation?

Delaplane

I guess I'm still working on it. I've got a lot of vacation time piled up at the Chronicle from past years. They’re now trying to figure out what to do about it.

Mosher

They could give you money.

Delaplane

Yes, I've suggested that to them, and they are going to give me some money. What we're in doubt about right now is just how much they will give me. I have one figure, they have another. Theirs happens to be a little lower than mine.

As far as the administration stuff is concerned, you handle it, I believe, like everybody does. Gradually each thing comes up and you do that particular thing, and it works out all right. But that's true of everybody. What the hell, the plumber has his worries, too. How does he get to this place in time? How does he pay to get the kids' teeth straightened? Whatever may be the problem. This is no unusual thing. There are certain things that man has to field, whatever business he goes into.

Mosher

One of the things for which you are somewhat famous is Irish Coffee.

Delaplane

They've got a plaque down at The Buena Vista. Did you ever see it?

Mosher

Yes, I've consumed Irish Coffee.

Delaplane

They put up a plaque and the Irish government is grateful. Every year they send me a bottle of Irish whisky or half a smoked salmon. That's what I've gotten out of it, although many people think I own The Buena Vista, that I've made it, all that sort of thing. But this is not true.

Mosher

You're not setting a percentage on all those drinks?

Delaplane

I'm not getting a percentage, no. It was in the winter of 1950, and I was going to Holy Year with Bob Considine, a well-known guy in the newspaper business, a Hearst man. We got stuck in Ireland because we blew an engine on the way over. It seems to me I was always riding on airplanes that blew an engine. I was frightened to death all the time. Riding in an airplane with four engines was terrible enough, but when they got down to three I was prepared to. . .

They were flying over a bunch of newspaper guys—Earl Wilson, Bob Considine, me—a lot of name guys. They also had a bunch of priests on board. I've got a priest sitting next to me. Every time we'd take off—we stopped everywhere for gas, New Foundland and a lot of places which I'd been writing stories about, places where they'd killed people—every time we'd take off this priest would cross himself. I thought, Holy Mother. Then we lose an engine! The guy was crossing himself, and now he's doing a few laps around the beads, too. "Holy Mother" or whatever it is. "Holy Mary, Mother of God."

Mosher

You joined him, so to speak.

Delaplane

Well, I wasn't sure. I thought maybe he’d take me by the hand and . . . Anyway, we stayed in Ireland for a while. Shannon Airport at that time was a couple of Quonset huts. We got some Irish Coffee there, so I wrote about it. A year later I was over again, and I wrote again about Irish Coffee. The next year I didn't write about it because I thought I'd done enough of this grand drink. I got a bunch of letters saying, "Why didn't you write about Irish Coffee this time?" Isn't that interesting? It's the only time I've ever had people say, "Why didn't you do it?" So, as I was going over every year, sometimes twice a year, I wrote about it again.

Mosher

This was in the ‘50s?

Delaplane

Yes. Then one night I went down to The Buena Vista, which was at that time kind of dying. I think there were three guys on the stools that night. There was me, Tom Rooney., who runs the Sports and Boat Show, and a real drunk reporter that we had; he would drink anything as long as it had liquor in it. He was down at the end of the bar. I was trying to make Irish Coffee for Jack Koeppler, the owner of The Buena Vista, but I couldn't make the cream float because Irish cream is thicker and heavier. I made about three of them, and the cream kept slipping down through them. We'd send them down to this drunk reporter, who'd drink anything, and he drank them.

Mosher

This was the first Irish Coffee mixed there?

Delaplane

Yes. I told Jack, "I don't know what the hell is the matter. I know that it floats in Ireland." We figured out the cream there is heavier. Of course, the more sugar you put in it, the more "lift" it has. There's a word for that, but I can't remember what it is. It rides on top better if you've got a thicker substance below. So, Jack put it in a mixer for a couple of seconds, just enough to float it, which is the way they do it now. It wasn't really whipped cream, but at least it would stay up, it had enough air in it.

Then people started coming in and trying it. I didn't write about The Buena Vista at all. People think I did, but I never wrote about The Buena Vista in those days as a place where you could get Irish Coffee. The word just went around. Pretty soon, jeez, you had cars outside, mink coats coming in after the theatre, and things like that. Jack Koeppler regarded this as a Holy War of some sort; I don't know why. He enlisted all kinds of people to help him, media people who were down there drinking. He went up to Reno and made Irish Coffee for the gambling joints up there. But I never wrote about it. I've written about it since, but I never wrote about it in those days. I had nothing to do, really, with making The Buena Vista famous. All I did was make the first Irish Coffee, and they took it from there. Now they sell three cases a day or something like that.

Mosher

Oh, it's an enormous item, I know. What do you think of it personally as a drink? Do you make it here at home?

Delaplane

I drink it once in a while when I'm in Ireland, but it hasn't got quite the flavor to me as those first few times when I was over there.

Mosher

You said at one time that the consumption of Irish whisky at The Buena Vista jumped from two cases to a thousand within a year.

Delaplane

I think it's better than that now.

Mosher

Before we leave this aspect of your life, let's talk for a minute about well-known people or names that you've come across.

Delaplane

I don't run across many names, and I don't use many names. I don't seek them out. In fact, I duck them a good deal. I figure somebody else is writing that type of thing, so I don't interview prime ministers. I don't interview movie stars. I don't run into many people who get their names in the paper. I'm usually writing about somebody who tells me an interesting story in a pub in London, or a guy in the Philippines who runs all the gambling games, whom I know pretty well. These people interest me for some reason, I don't know why.

The guy whose picture is over there is named Ted Lowin. Teddy had been a gambler and a bootlegger in Albany, New York, and had been in jail many times for short periods. He’d do a job in Albany for bootlegging or gambling or something like that and he’d wind up in jail. When the Japanese moved into the war, he went out with the troops to Bataan in the Philippines. He may have joined the Army. Anyway, he was somehow there. But what he actually did was run a gambling game in a place called Little Baguio, which was a big camp out in the brush.

Ted was captured with the rest of the people and made the Death March. But he had very little trouble in Japanese jails because he’d been in so many jails he knew exactly how to handle it. He started immediately collecting things from people, bribing the Japanese guards, and buying this and that. He had a black market going inside Santo Tomas like you'd never believe. He did the same thing when they moved him up to Japan. He was a "dese" and "dose" guy, and he was fit to survive. I mean, being in jail again, so what? Japanese jail, Albany jail, same thing. Same kind of wardens.

I used to go over and see Ted all the time. He had buried $10,000 out in Little Baguio someplace. After the war he went back. He had made a kilometer marking, but the Japanese had changed the kilometer markings. When the Americans came back into Manila, they changed them again. So, he never could find it. The jungle had grown over it. He gave me a map to it and said, "If you can find it, it's all yours." It was in the old yellowback bills, the big ones, American dollars that he'd won in the gambling.

One time they were having a memorial march of the Death March, and I said, "Are you going, Ted?" He said, "Listen, I was in the original cast. I wouldn't do it again if they were to give me a limousine." That's the kind of guy I like to meet, a guy who can make a remark like that. I enjoy it, and it makes a good column. I wrote a lot of stories about Ted.

Mosher

Where is he now?

Delaplane

He's dead. He was quite a guy. He gave me that picture he bought it from some Filipino artist. That's why I keep it up there. It's not that it's such a great picture, but it reminds me of Ted.

Mosher

I can understand your feeling about it. You've written about somebody at the Mapes Hotel in Reno a number of times.

Delaplane

That was Walter Ramage. He was the kind of guy I can bring up in a column. Somehow, I can't bring up a movie star. Sometimes I might be able to, but mostly I can't. I can't take a guy like Sinatra, who I've talked to, and bring him up. I can do better with a guy who's not so well known. I don't mean I'm reaching for little guys or that I'm playing the little man's spokesman; it's not that idea. I can just get it better. The well-known guy is a little colored already by so many press agents who pushed him on me so heavy. Already I've got a picture of him. I can't paint it myself. The canvas is already covered with somebody else's paint. I did do a thing with John Wayne once. Nice guy, real pleasant. I had a pleasant time with him. But he was so colored himself by his own press agent. He's not a guy who's hard to talk to, and he's not colored by thinking he's a great man. But he's been interviewed so many times he is colored to me— and maybe he's colored to himself he’s been interviewed so many times. I couldn't get what I wanted out of him, whereas with a guy like Teddy I could.

Mosher

The real person, if indeed there is one, is often buried.

Delaplane

I think people who are covered by a great deal of publicity are colored a good deal. They're a little shy about, "What's going to happen to me?" I'm doing it right now, while I'm talking to you on this tape. I'm thinking a little bit all the time about how am I going to look on it. These are things that make it a little difficult to talk to a guy – and a little more easy – like Wayne and a little easier to talk to a guy who has had no exposure at all and doesn't really care whether he's going to get exposure. It gives you a little better picture of what his life is like. You don't have to dig through a lot of the overlay of varnish that's on him already. It's all pure wood that you're carving into.

Mosher

Well put. Let's talk about your background a bit, where you were born and when, that kind of thing.

Carmel with Artist Mother

Delaplane

I was born in Chicago. I went to school in Monterey [California]. We actually lived in Carmel, but I went to Monterey High School; we had no high school in Carmel at that time. Carmel was a pretty small town, about 1,000 people I'd guess; 1,500 at the most.

Mosher

What was your father's occupation?

Delaplane

He was a real estate man, but I was not raised by my father. I was pretty much raised by my grandmother. My mother was an artist and was off to various places. That's how I got to Carmel; I went out to live with my mother. The town was full of very big names. They had more Pulitzer Prize winners in Carmel than they had in the whole country, I think. It was just full of really big names.

It was a small town, as I say, and these people would come around at night. There were no movies in town. There was a movie house over in Monterey, but there was no other place to go. They would sit around and play poker and drink a little bit. Bootleg days, you know. I'd hear these stories about the time when they were on the Chicago Tribune, and how they covered a story, and so forth. They were out of the Ben Hecht-McArthur era. They talked about things that sounded fascinating to me. That's how I got into the newspaper business. I thought, Gee, I've got to do this thing myself. I mean, these guys really influenced me. Of course, they had been long out of the newspaper business, and I didn't realize that what they were talking about was their youth, not the current newspaper business. Nevertheless, they put me into it with that chatter of theirs. I've spent the rest of my life trying to get out of it!

Fortunately, I got a sort of back-door parole, in a way. I no longer have to be a reporter. I found, after World War II, I'd had it. By God, I'd run my course on that sort of thing. I was able to get out and become a columnist, which kept me in the business but also let me get out of it—at least get out of it from the standpoint that the newspaper business requires certain stringent things about how you write. You have to get everything in the lead. It doesn't let you write very much. It doesn't let you write about yourself. It doesn't let you write about a lot of things like that. I found I'd done it too many times. It was "Joe Shoots Mary," "Mary Shoots Joe. What? Over the Biscuits." The same thing over and over.

WORLD WAR II AS WAR CORRESPONDENT

Mosher

It's kind of a formula, I suppose.

Delaplane

It's really very interesting when you're a kid. It's the best way to learn. If I had a kid who wanted to write, I'd put him in the newspaper business for five years for an education. You find out how the town works, how people work. You find out how people feel about things. It's really a hell of a good education. But you've got to get out of it at a certain time.

Mosher

Speaking of education, you went to school in Monterey.

Delaplane

I was living in Carmel, and I wasn't doing too well in school. My mother was living down in the Ojai Valley. I was living with some people I'd sort of been left with. I don't know what the hell was going wrong, but I figured I wasn't going to go anywhere, so I dropped out of high school in my last year.

I knew some people in San Francisco who got me a job as a cadet on a merchant ship, and I spent a year as a merchant cadet, deck cadet, going up and down the coast. It would take us three months to get from San Francisco to Panama and back, we'd stop so many places. We were carrying dynamite for the mines, barbed wire, and we'd pick up coffee. We'd stay in a port maybe five days. If there was a banana ship coming in with spoiled cargo, we'd have to pull away from the dock and they'd go in. I went into places you've never heard of. Did you ever hear of a place called Puerto Angel? Nobody’s ever heard of Puerto Angel. We used to spend five days in that place. It had one cantina, about five houses, and a whorehouse. That was Puerto Angel. I'd spend five days there drinking beer. It was a pretty good life.

During World War II I was in the Navy. They put me in a computer and found I had a merchant marine background, so they sent me back to Washington to be a public relations guy for the Maritime Commission and the War Shipping Administration. I was sort of a PR guy for five admirals—for Joe Kennedy, too, Jack Kennedy's father. He was part of the commission. So, I had five admirals going for me, plus Joe Kennedy. That's how I got out of the Navy. I got on inactive duty because they were going to send me to Calcutta as a port director, and I didn't want to do that. That's how I got to be a war correspondent for North American Newspaper Alliance and the Chronicle.

Mosher

What year was that?

Delaplane

That was 1943. I went out in late 1943. In '44 in New Guinea. I was in the invasion of the Philippines, and then they pulled me back to do the United Nations Conference. They sent Carlos Romulo as ambassador to the United Nations from the Philippines, and Carlos and I both won a Pulitzer Prize the same year. I knew Carlos pretty well, "Rommy," we called him. I still know him pretty well; I go and see him when I'm in the Philippines. I spent most of the time back here in the United Nations Conference. I had kind of a finger in through Rommy, who seemed to know what was going on.

Mosher

When did you move to Marin County?

Delaplane

Right after World War II I came over and rented a house in Belvedere. Housing was pretty hard to get in San Francisco. I was married and had a small child, about three years old, and this seemed like a pretty good place to be. I moved over here, and I've stayed with it.

At Home: Sausalito

I was having to commute to San Francisco as a reporter at that time. It seemed to me it was a pretty good deal. As a columnist it's even better. There's no point in my living in San Francisco. I don't write about San Francisco. If I want to do the home stuff, Marin has a better circumstance. I can do a little bit of the wild stuff of Marin—the Sausalito scene, the gurus, the astrologers, and things like that. I was very glad when that NBC special came up [I Want It All Now!], with the peacock feathers and all that kind of stuff. It sort of backed up the thing that I'd been saying that Marin was kind of a goofy county. Although, as we know, there are parts of it that are very straight-arrow. But there is also a sort of wild fringe, save at the Trident in Sausalito. I go over and eat at the Trident every once in a while just to sharpen my wits.

Mosher

And there you see and hear the type of person they were talking about on the TV show. I guess you would agree then that Marin County has been out in front in a lot of social talk and personalized experiences and so on.

Delaplane

I think a lot of people have read about Marin County. I've certainly done my best to have people read about it, and I think I make it sound attractive. I don't think people come over here expecting to find a lot of dope peddlers and things like that. They come over here feeling it's kind of a lively place. It's got a little spirit to it. Marin to me just has a nice feeling. I like the place, and I live well here. I've adjusted to it. For the type of column I'm writing, I need a home base. As I say, I don't want to be an overseas expatriate. I want to spend some time overseas, but I want people to feel I'm writing as though I am an American, living in a certain place with certain things around me. I use cats, dogs, and children a lot. It feels right to me, and it sustains me as well as the reader.

Mosher

You were talking about the articles you're going to write later on, presumably with the material on cocaine. I think Marin County is sort of avant-garde in that area. I was recently doing a tape with the chief of police of Mill Valley, and he pointed out that Marin was considered, along with one or two other places in the world, one of the main dealing areas. I think it's certainly true.

Delaplane

Yes, I guess it is. I don't know. I don't do crime type stories, so I don't run into it a hell of a lot. I don't push it into a column much, either.

Mosher

It doesn't fit into your type of thing, really.

Delaplane

If I found some kind of interesting angle for it, I would do it. Like Frank Werber over at the Trident, who is doing six months for having a backyard stacked with pot. I used to write some stories about Frank once in a while. He was a pretty interesting guy. He talked well; I enjoyed the way he talked about things. He had some sort of goofy outlets. When I say goofy, I mean they were entertaining.

Mosher

What do you read in your spare time?

Delaplane

I have a stack of magazines. Here is this week's stack. I get about ten different magazines. I can't read all of them; I keep trying to cut out things that I want to read. I get three newspapers a day. I try to leaf through them and keep an eye on what's going on. I get some overseas stuff from time to time. There's a weekly newspaper in New Guinea that's written completely in pidgin; I get that. There's some interesting stuff in it. I ran into a story down there which I will get into sometime when I go back. I haven't written it yet. There are quite a few Japanese coming back to New Guinea now to see where father fought the war. Father takes them back and says, "This is where I was." You remember we bypassed a whole Japanese army at Wewak and went around them. They were stranded there. They raised little gardens of vegetables to keep themselves going. There was a guy down there who had been in the war for the Americans, and out there at Wewak he ran into a Japanese who had been in the Japanese army. He was down there with his family. They drank some beer together, trying to talk, but neither of them spoke the language. The American finally said, "You savvy pidgin?" The Jap said, "I savvy pidgin," and they got along great together. You know, "Talk, talk, too long you belly my belly." They did the whole thing in pidgin. That’s the kind of story I like to write.

Mosher

I’m going to ask you a final question. If you had a three-month, prepaid vacation with no deadlines, in view of all your traveling where would you like to spend it?

Delaplane

Since I haven't had a vacation for twenty-five years, that's a good question. I really don't know what I'd do with time to spare like that. I think I'd try to backtrack on a lot of things that I keep wanting to do and don't, but it would be part of the column operation—things that I'd like to have just a little more time to work on. I'd probably do it in some country where I can speak the language. This is kind of important. I don't think I'd spend any time in the Orient. I'd spend it maybe in Spain and Mexico and England, where I'm comfortable.

The big problem is communication. I can speak Spanish pretty well. I can speak French pretty well. And English, of course. But if I get into Greece I can't even read the signs. Same in Russia. The problem is, if you want to talk to a guy, say you're riding with a taxi driver in Tokyo, I can tell him in Japanese, "Turn right, turn left, go straight ahead, stop here, I want to go to the Press Club and it's near the Nihombashi Bridge." I can tell him all that in Japanese. I can call a cab in Japanese. I know the numbers. But I can't talk to the guy and ask him, "How do you like your job?" There's the problem.

They only have so much money that they have to keep their fares going, so they drive wildly and outrageously. I know the guy's got that problem, but I can't ask him how he got that problem. I know it from somebody else; some Japanese has told me. But I'd like to ask the guy. I'd like to say, "How do you like your job? Where do you live? What do you eat for dinner?" Things like that. But I can't say it. I can say it in French and in Spanish and in English, so if I can, I like to go to places like that. I'm really at home in Spain or Mexico, with no problem. I can do the jokes. I can do the Bob Hope show! That way you can get a thing going back and forth with the people you talk to. Otherwise, you're dead.

Mosher

Well, Stan, on behalf of the Mill Valley Historical Society, and most particularly me, I really appreciate your taking the time out of your schedule to do this. It's been a great pleasure.

Delaplane

Thank you.